Welcome to our newest blog series dedicated to the research we're reading and thinking about.

The last time I was at a family function, I was excited to catch up with my 15-year-old cousin. I hadn’t seen him for a while, and I was ready to get clued into the high school world. Sadly, he had other plans, most of which involved watching YouTube videos and responding to my questions with, “sure,” and “cool, Allie.”

Let’s be honest—I didn’t take it personally. I do ask a lot of questions, and whatever the setting, teenagers are notoriously difficult to engage. My secondary-level teacher friends assure me that this extends to the classroom, where they work hard to encourage behavioral, emotional, and cognitive engagement. These aspects of engagement are distinct, but related, so all three are crucial to fostering student success.

Naturally, there is a lot of professional development to support teachers’ efforts to better engage their students. But very little of it is has been backed up by research. In fact, of the 1,300 studies examined by What Works Clearinghouse (an initiative by the federal Department of Education that reviews research evidence on topics related to education), only nine met their quality standards. This prompted a new, rigorous study in 2014 of the MyTeachingPartner-Secondary program (MTP-S) on student’s behavioral engagement, which includes classroom participation.

Researchers used a randomized control design (or RCT) to test three questions: how does MTP-S affect students’ behavioral engagement? How do other relevant factors play into this effectiveness? And how, if at all, do these changes work through the lens of CLASS-Secondary (CLASS-S)?

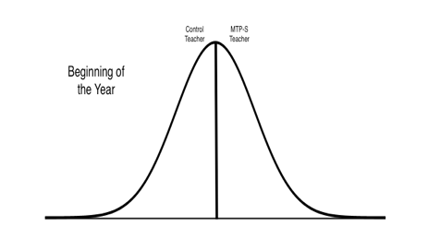

Eighty-seven participating teachers from 12 Virginia middle- and high schools were divided into two groups. An intervention group in which teachers participated in two-week-long feedback cycles with MTP-S coaches. And the control group, in which teachers continued their usual professional development but still recorded six lessons across the school year for researchers to watch and analyze. The two teacher groups were statistically identical. On average, teachers had eight years of classroom experience and most were Caucasian (as were their students). Observers coded the videos using CLASS-S, which includes Students Engagement as a global measure of student functioning. Researchers used ratings from the beginning of the year as a baseline against which they compared end-of-year engagement.

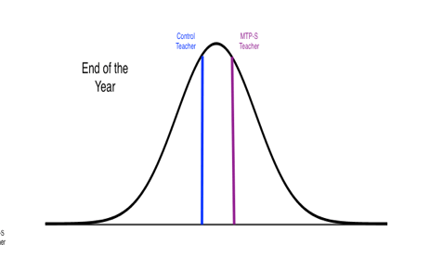

Intervention group teachers showed a substantial advantage over teachers who participated in business-as-usual professional development. Control group teachers showed, on average, a loss in behavioral engagement from fall to spring. But teachers receiving MTP-S coaching showed a gain of approximately the same size, ¼ of a standard deviation.

Here’s an illustration of what that means. Two teachers—who teach the same subject and the same grade level—start off the school year with average behavioral engagement. Over the year, as kids (and teachers!) get restless for summer vacation, a classroom where the teacher continues her normal professional development schedule gradually shows a decrease in student engagement. On the other hand, the teacher who is receiving MTP-S coaching sees an increase in participation from the beginning the year, and her behavioral engagement rating actually creeps up above her initial, average-level engagement. By the time they reach the last few weeks of school, there’s actually a pretty substantial difference between these two classrooms. Even though they started off in exactly the same place!

In addition to the direct effects of MTP-S on students’ behavioral engagement, researchers looked at CLASS scores to see if any of this change was related to particular dimensions. They found that intervention-group teachers showed increased scores in Instructional Learning Formats and in Analysis and Problem Solving. These increases were also related to higher behavioral engagement, which suggests that these dimensions indirectly affected students’ engagement. Basically, MyTeachingPartner coaching led teachers to improve their use of varied instructional practices, active facilitation, and use of activities that required higher-order thinking skills. This, in turn, supported students’ behavioral engagement.

Even though these effects are relatively small, it’s a pretty exciting result! This is in line with some earlier, more basic research that links challenging classroom activities with higher engagement, and the rigor of this RCT means that their conclusions are well-supported. The authors suggest this as a possible mechanism of change: teachers who give students more interesting and advanced work and support it well through their own practices help students “check in” to the classroom.

Apart from the direct benefits of more engagement, being behaviorally, emotionally, and cognitively present at school is linked to long-term outcomes, like educational persistence and job success. Engagement also contributes to school climate, which, in conjunction with other social-emotional supports, can reduce academic disparities for students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds.

So teachers, take this as your encouragement to try out those tougher lessons. It just might help you reel in your middle and high school students.

Citation: Gregory, A., Allen, J.P., Mikami, A.Y., Hafen, C.A., & Pianta, R.C. (2014). Effects of a professional development program on behavioral engagement of students in middle and high school. Psychology in the Schools, 51(2). 143-163.