How should you begin thinking of equity as a verb? What are the first steps for businesses and schools to take to create change? What steps can educators do within the classroom to be more mindful and culturally competent?

In today’s episode of Impacting the Classroom, you’ll hear a conversation between Dr. Darlene Estes-Del Re, Marnetta Larrimer, and Dr. Rosemarie Allen. Dr. Allen is the President and CEO of the Center for Equity and Excellence and has a 30-year background as an educational leader on a mission to ensure that all children can access high-quality, developmentally appropriate, and culturally appropriate early childhood programs.

Listen in to learn what the effects of the recent push for more equity have been, what an equity audit is, and how the American Rescue Plan funds can be used to support the effort for more equitable classrooms.

Darlene: Welcome to Impacting the Classroom, the podcast where you can listen to dynamic interactions among educators, policymakers, and researchers who are making an impact in the classroom. I'm Dr. Darlene Estes-Del Re.

Marnetta: I'm Marnetta Larrimer. Today, we're jumping into an important topic. I've really been looking forward to having this discussion: how to build a more inclusive and equitable education system. I am beyond excited to introduce one of my favorite people, who I know will have a lot of things and thoughts to contribute to this subject, Dr. Rosemarie Allen.

Dr. Rosemarie Allen is the President and CEO of the Center for Equity and Excellence. She has served as an educational leader for over 30 years. Her life's work is centered on ensuring all children have access to high quality early childhood programs that are developmentally and culturally appropriate. She is currently an associate professor in the School of Education at Metropolitan State University of Denver where her classes are focused on ensuring teachers are aware of how issues of equity, privilege, and power impact teaching practices.

Dr. Allen also serves as the president and CEO for the Institute for Racial Equity and Excellence, IREE if you want to look that up, which is the lead agency for ensuring equity in educational practices throughout the nation.

Darlene: Welcome, Dr. Allen. I'm with Marnetta, super thrilled for this conversation. I know all of our podcast listeners are going to be equally excited and thrilled to know that this is just going to be a really organic conversation about this topic today. We're going to leave being enriched by this conversation and inspired. I get the pleasure of kicking us off with the first question.

We've been hearing a lot more about diversity, equity, and inclusion over the last year or so since George Floyd’s murder. There was an initial flurry of work that muscled up from that to create a more equitable system. It seems like schools and education companies have continued the work. But I'm curious, Dr. Allen, if you think the needle has moved and whether children—particularly children of color—have seen direct improvements from this recent push in emphasis on equity?

Has the Equity Needle Moved?

Rosemarie: First, I want to say thank you, thank you so much for having me. It is an honor and a pleasure to be here, especially to have these conversations that are avoided by so many. Yes, the murder of George Floyd revealed systemic racism that has been long-term and ongoing, actually, since the inception of the country. Once it was revealed, people seem to be surprised and overwhelmed by the vehemence of the people of color—specifically black people, and the fight for equity, and the fight for justice.

Once people saw it, someone asked me once, what was the difference? Because we've had murders before. We've had murders happen. I can just give you a list of names, but the murder of George Floyd hit differently and people ask, why?

This is a Rosemarie-ism. I believe that we were already in this triple pandemic. Those people were at home. Remember, it wasn't like it is now. During this time, we could not leave the house except for essentials. So, people were quarantined, mandated to be at home, and many people were struggling. So that was one pandemic. Then the whole economic pandemic where people could not work and lost their jobs. Then the racial pandemic, so people were at home.

When this recording of the murder of Mr. Floyd happened, they couldn't look away.

It was one of the first times that you were stuck. You didn't have a lot of distractions. You couldn't say, “Oh, I don't want to look at this,” because it was everywhere. I believe it was one of the first times that we saw the actual murder. Because so many died later, but we actually saw the knee on his neck until he took his last breath.

I believe every mother in the world had a collective reaction. When, as he was dying, he called for his mama who had died just six weeks earlier. And, I believe that’s what hit us differently. It really resulted in a call to action that was worldwide.

Since this happened, changes have taken place across the globe. People now understand better, some people, that there are inequities in our society, and black children on every single indicator of well-being are at the very, very bottom. People have begun to realize this. We're seeing organizations, institutions, agencies, especially educational agencies, wanting to make a difference.

Before the murder of George Floyd, lots of my work was one-and-done workshops, hit and miss workshops, keynote workshops. I have to say over the last year, that has changed tremendously. People are saying we want to dig deeper, we really, really want systemic change. They want to understand the difference between individual racism, institutional racism, systemic racism, and to make changes at the systemic level. Because of that, Darlene, we are not seeing the needle move yet for children because this is a process.

That process begins first with the individual to say, “I am a biased, racist, flawed individual, and the impacts that I have on children can be negative.” Then to say, “And I work for a biased, racist, flawed institution,” and we have to do something about that. Then to say, “The institution that I work in is part of a web of institutions that are biased, racist, and flawed from social services, to healthcare, to law enforcement, to our judicial system. My system interacts with those, is intrinsically tied to those, and I have to do something at that point.”

We can't measure it yet because if we do, whatever results we see will be fast because it takes a while to really impact systems. But what I can tell you is that I've seen a change in the behaviors of people and understanding of people. We're seeing more positive impacts directly with children and families, how they're viewed, and how they're interacted with. So we're seeing changes there, but we do have quite a way to go for institutional systemic change.

Darlene: I deeply appreciate that. I think too, in my own journey on this path, when I hear systemic racism, I thought about systems, I always have, but I didn't really think about it in the way that you described that. We sometimes don't just envision all the ones that interconnect, like you said, how they all come to interplay and just then the collective impact that has as well.

So I just appreciate you pointing that out and helping us to realize there's a lot to unpack. There's much to do, and then if we do it really well, we're going to see those impacts coming to the children who most certainly deserve it, and then it'll be a lifetime change for them too. I certainly appreciate you setting the stage for this conversation. I'm going to kick it to Marnetta for the next question.

Marnetta: I think in hearing just what you said, you're right. As a black woman with two black boys, my heart broke. I think the awareness that came around George Floyd's murder was very eye-opening. I live in a neighborhood I've lived in for 20 years that my children can't go out and jog in, even though we've lived here for 20 years.

It's like you said, there are things that are changing. I have neighbors who might speak now or whatever, but it's been slow. It's still progress, but it's very slow-moving. But like I said, it's been 20 years that I've lived here. How long do I have to live here as a great citizen before I’m acknowledged as being worthy of engaging in just regular things like jogging around the neighborhood?

The First Step

Marnetta: My question for you would be, as we think about these systems, how they're integrated, and the biases, challenges, and barriers for people of color, what would be the first steps that you would recommend for an organization or a program to design and implement equity-focused programs? That could just be in general or around the American Rescue Plan Act funding that's coming down, but what would you recommend?

Rosemarie: Absolutely. The first is to conduct a temperature check. Who are we, who do we say we are, and who are we really? Because right after the murder and the civil unrest, people began to create amazing, beautifully worded equity statements and mission statements. That's great. That's a start because it's saying this is who we want to be, but are you really?

How are you living out your mission, vision, and value statement? So the first step would be to engage in an equity audit. Let's take an audit of your practices, policies, rules, and see where barriers are that prevent people of color. I'm not going to just say children because in order for children to do well, the workforce must do well. So let's just take a look at who we are.

What's included in an equity audit? First, an equity audit might say we value racial equity, we will put procedures in place that will elevate this, and we value a diverse workforce. Let's look at the workforce. If that's who you say you are, let's look at your workforce and see based on positions where people of color are and are not. I believe that 70% of the early childhood teacher workforce are women of color.

They are women of color and there are unconscionable wage disparities, especially between black, Hispanic workers, and white workers. Same positions are paid about $1.12 an hour less for black women in the same position. For Hispanic and Latinas, they are relegated to the lowest level positions as assistants, as teachers aides, usually in the infant room, and black women as well. It’s reminiscent of Antebellum South when they were wet nurses and had to take care of babies.

When we think about history, what has happened? Very little room for growth. You see, black and brown women in those direct care positions, but the higher up you go, the fewer you see. In many situations, the leadership is all white.

So if you value diversity and then you take a good look at your workforce, what does that tell you? If you value diversity, you work in an affluent area, and a small percentage of your children are of color, what does that tell you? If you value diversity, but your parent organizations and support systems are predominantly white, what does that tell you?

When you conduct an equity audit and you talk to your workforce of color, your people of color, and they say they can't be their authentic selves, that they're forced to code-switch when they come in. Code-switch means to change who they are to assimilate and be accepted in that work environment, or say that they have very little room for growth. That equity audit will give you so much information. So that's the starting point.

Then next, you take the data and create a comprehensive plan on how you're going to impact change. That is the hard part because for instance, let's take the workforce. I was working with an agency in Chicago and the principal of the school has such a heart for equity. Just amazing.

He said, Rosemarie, I don't understand why all my paras [paraprofessionals] are people of color and all my teachers are white. I just don't understand that. I said, what do you think is happening? He said, it's very hard for me to find people of color who are qualified. Let me tell you, that is the biggest myth in America.

Marnetta: You saw my face.

Rosemarie: The biggest myth! There are highly qualified people of color in every sector of the system. You have to know how to recruit them and then how to retain and support them. Anyway, he said, I just can't find any. I said, okay, well, let's take a look, why don't we first do an audit of your files of qualifications?

We went through every staff member’s file, looked at all their qualifications, and 60% of his paras have master's degrees.

He said, I never knew, I didn't know. I said, so here are your qualified people. The question is, why didn't you see it? This isn't to blame or shame. You all know me. I don't believe in blaming or shaming, but there comes a time when you have to look inward and be very honest about what you see because this is what happens across the country.

You have people who go to school, they take out student loans, they're trying to elevate and engage in this upward mobility, but they're never seen as anything except a para or except an aide. So when these positions come in and they interview within their own agencies, the bias of the agency keeps them in the box where they believe they do.

To answer your question, start with the equity audit, then address some of the deficiencies. But also engage in long-term systemic training that's going to, as you asked earlier Darlene, move the needle. At the end of that year or two—after the training, and implementing policies, and looking at your practices—then conduct the exact same audit. I say 18 months to 2 years to see where that needle has moved.

Marnetta: That was a powerful response. I had the feels again because you're talking and it's like you're saving my life and what my journey has been because it is very challenging. People get very comfortable because that's what they're used to seeing. The women of color, how do you have a job? You got to feed your family. We're doing what we need to do, but then you start believing this is all it is because that becomes the norm for you. Then we get into that internalized oppression, and that's a whole another cycle. That's a whole other conversation that we could go into.

Rosemarie: It's really amazing because it happened to me. I directed our lab school. I was at a community college and I really wanted to move up in higher ed. I continue to apply for the position of Dean, but they could not see me as anything other than the lady who takes care of the babies across campus.

It was so bad because I turned inward as well and I said, well, maybe it's because my degree is early childhood. Let me go and get a master's in education. So then, I invested in that just to show them I could do more. In order for me to move up, I actually had to leave that college.

Marnetta: Yeah, that's how I got here. That's a whole other story. That's how I ended up at Teachstone just because you have to recognize when there's no growth. We as a people, we have to recognize where we're not being seen, not being represented, and that needle isn't moving. Just know that there are places you can go that are feeding into this work, really recognize, and are leading with the intention to put you in those spaces that you didn't think that you could get into.

Creating Widespread Change

Rosemarie: Absolutely. That's on an individual basis. If you don't mind, I want to go back to the use of some of the American Recovery [sic] Plan. I talked about the equity audit, and we just talked briefly about mobility and what that looks like. What is going to take for us to really impact change using those recovery dollars is to look at things differently and with a new lens.

I just have to say, there are states who have already unveiled their plans. It broke my heart that so many never ever mentioned racial equity, not in the plan at all. When you look at this administration's goal, President Biden has been very clear about racial equity. These funds can really, really make a change. For instance, here in Colorado, they put the funding in three buckets, access, workforce, and family strengthening.

You can't talk about access without talking about the inequities in access. I'm going to take you back a little bit. Every agency has relied on three studies that took place in the ‘60s to talk about the cost-benefit of early childhood education, the Perry Preschool Project, Abecedarian, and Chicago Child Study. Those three studies were conducted on primarily an all-black population.

Perry Preschool project, 100% of the participants were black families. Chicago Child Study, I believe is 97%. Abecedarian, 93% were black. We have to look at the racial backdrop of those studies. Those studies were not conducted to improve the quality of early childhood education. Those studies were conducted to fix the inherent deficits of black children because they were believed to be inherently deficit.

Think back to the 1960s. These children, we have to teach them how to be citizens of our country, and their IQs are inherently low. Especially Perry Preschool Project was to increase IQ scores. They thought that parents were not equipped to raise their children, that they were pretty much inept. Just take a look at how they have that white card. It’s really clear why they put this study in place.

The study was conducted from this pathological lens and the way that black children and black families were viewed. We had amazing outcomes from that. We know that there were long-term benefits in terms of increased achievement over time, decreased teen pregnancy rates, income, long-term jobs, all of the benefits. But imagine how much farther we would have been had they seen the children of families from a strength-based lens and actually talked to the families about their goals for their children.

Talk to the teachers. Louise Derman-Sparks, she was a teacher in the Perry Preschool Program. She talks about how they never talked to them about how well the children were doing. They didn't get the teacher's perspective. Why do I go back to that? Because we can learn from that if we want to do better. So those same children who gave us the data on the importance of high quality and early childhood education are the same children today who cannot access high quality early childhood programs.

Marnetta: How long has that been? When we talk about the needle, it's not a walk. We're talking snail pace, slow inches. That was a long time ago. It's the same challenge.

Rosemarie: They cannot access high quality programs. When they do, they're pushed out to suspensions and expulsions. There's something wrong with using the data of people that have been proven to work and not allowing access. When we look at access, we have to look at how few children of color, specifically black children, have access to high quality early childhood programs. So that's one.

Then the workforce, we talked about a little bit. I've seen states come up with amazing things—free education to help teachers become qualified. That is amazing, but we can't ever apply colorblind policies. Because what will happen is those who stand to benefit the most will be left out. So what are we going to do to make sure our indigenous, Hispanic, Latina, African-American populations not only access the funds but are in cohorts to support each other with teachers who understand?

Are we going to offer these classes in different languages? Things like that. That's how we're going to move the needle and then family strengthening requires us to see families differently. You know what we'd love to say in early childhood? Parents are the first and best, most consistent teachers of their children. If we believe that, why are people so up in arms about learning loss over the last year and a half?

Marnetta: You must want to come for another session because you're talking some things.

Rosemarie: Is that amazing? If they were with their best teacher, how did they lose learning? Because they were their best teachers.

Marnetta: When you mentioned that, it just made me think about the pandemic, again, in a different way and equity in a whole another way where we have children learning at home. We have companies creating products where children can enhance their learning, mitigate learning loss while they're at home. We are even going to give them technology, but then we forget that they don't have internet access.

Why can we not think as a whole, in big-picture thoughts, when it comes to mitigating equity problems? It's always like checking a box. I'm going to do this, this, this, but we're not really ever digging really deep to make sure that that is truly accessible.

Rosemarie: Marnetta, we don't talk to the very families we're serving. What do you need? They may tell you, my child is accessing this on my phone because we don't have a computer or a laptop. Then in some situations, some schools are giving one to every child and they already have one.

Some don't have high speed internet. So I think, talking to the families and finding out what their needs are, but not only their needs, what their strengths are. A girlfriend of mine, during this period, she posted a video of her child and he was learning math. Every time he got a problem right, he jumped up, danced, and then backed down. Then that's when he jumped up and danced, and she says, this is my situation right now.

I thought, how awesome for him to be motivated in that way. But what happens when he goes back to school and he gets the problem right and he jumps up and dances?

Marnetta: Sit down, go to timeout. We're not having that, right?

Rosemarie: Yes. Now, all that black boy joy is gone because he's penalized because he's celebrated with being happy and engaged in learning.

Marnetta: He doesn't get to be his authentic self in the classroom. He has to conform and learn how to survive in this space.

Rosemarie: Absolutely. When I talked about the way that we viewed parents in the ‘60s. Is it reminiscent of the way we're viewing them right now? These children have learning loss. We need more mental health consultants for when they come back. They've been out of control. They've had no rules.

That translates into these parents didn't know what they were doing, instead of really talking to the families and saying, “How did you motivate your child? What excited them about learning? When did they need breaks?”

My two children, if they didn't eat every two hours—little bitty things—my daughter is 38 years old. I don't think she's 100 pounds yet, but she eats like crazy, and they would get hangry. You'd have a hard time with them.

When does your child need to eat? Do they need snacks more often? What has your schedule been like? They want to move the needle with family strengthening and equity. We partner with families who are the child's first, best, and most consistent teacher to get the best outcomes.

Marnetta: Yeah, and those things that we offer have to think about where the family is at. It can't be from 8:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. Everybody doesn't work from 8:00 am. to 5:00 p.m. They don't work from 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. It might be something that we offer in the evenings, even including the care.

So in giving them access to quality care, it's not even just always about the money, sometimes it's about time. Like, I don't need care during the time that you have care available. How can I still have the support I need in hours that I need the care?

Rosemarie: Absolutely. I can't tell you how many families, just even before school care, have to be at work at 8:00 a.m., which means that the child needs to be dropped off at 7:30 a.m.. You can only drop your child off at 10 minutes to 8:00 a.m.

Marnetta: I’m not going to have a job in a little bit because I'm going to be late every day.

Rosemarie: Every single day. Those are the things that we need to take into consideration.

Marnetta: We talked about a lot of things and you mentioned earlier, we were talking about paras, co-teachers, and things like that. I want to know, what can we do to ensure and support the need for culturally competent early learning educators? What would your recommendations be?

Rosemarie: First, it's really going to have to start with training, with helping people to understand the cultural lens through which they see the world. That's just across the board. You think about the Brown v. Board of Education decision that happened in 1954. Today, in 2021, we're more segregated than we have ever been in this country.

You talked, Marnetta, about living in a neighborhood for 20 years that your child can't jog in. Even though you are in this, and I'm going to assume that's a predominantly white neighborhood.

Marnetta: By a military base.

Rosemarie: Oh my. That's a whole different question. We don't know each other. We don't know each other at all. We have this cultural lens that we use that drives everything we do. In order to be culturally responsive, you have to understand that the lens that drives you is not the lens that everyone has.

I'll give you an example. In my family, if an adult calls you, you come. Simple as that. If my mom said, “Rose,” I come. That's the way it is. If I'm coming, I say, “Coming!” Now, if an adult called me and I said, “What?” Oh my goodness, you're talking about big time trouble. I use this because it actually happened to me.

I worked in a predominantly black area when I lived in Los Angeles. When I moved to Colorado, 99% of my children were white and I'll never forget calling Connor.

I said, “Connor!” and he goes, “What?”

What? Surely, this little boy didn't say what to me. I said, “Connor!”

He said, “What?” I thought, oh no.

I marched right over there with my hands on my hips, got down to his level, and said, “Did you hear me call you?” He looked at me and he's so puzzled. He goes, “Did you hear me say what?”

He answered. His cultural lens, the expectations for his culture were so different from mine. It wasn't until I looked into his little face and saw how confused he was that I realized he didn't think there was anything wrong at all with saying, “What.” I'm unruffled because he said, “What.”

Do you see how that cultural lens can end up in cultural disconnects that can contribute to the disparities of black children being suspended more often than white children?

Marnetta: Most definitely. A lot of times, we're not honest with ourselves, and people aren't going to do self-reflection. You checked yourself. You're just like, oh my goodness. No, some people are going to hold firm to what they believe, and it's going to be about this is what's right, this is what I'm feeling, and this is what it is. They're not going to take the time to look at another perspective.

Rosemarie: Absolutely. Marnetta, what if I dug my heels in? He said, “Yeah, I heard you.” Well, why didn't you come? When I call you, you come. Connor was—woo!—Connor, he would have said, “Well, why do I have to stop playing to come just because you called me?” It would have turned into something different.

The first step is helping people to understand that cultural lens and having them accept that that lens is also biased.

Marnetta: Most definitely. Digging in, it damages the relationship. It doesn't tell the child that you like them or care about them. It's going to impact their learning because you can't teach me nothing, doctor. Dr. Rosemarie, regardless of what your title is, if I don't like you and I don't think you like me.

Respecting Names

Rosemarie: That relationship is critical, especially for young children. Then you have to help people understand the daily acts of bias that take place in the early childhood classroom like mispronouncing people's names. Marnetta, I cannot even imagine how many times your name is mispronounced.

Marnetta: And how many times they asked for a shorter name and I'm just like, no, it's beautiful. You're going to learn all the letters. Say all of it.

Rosemarie: All the letters, thank you. So not only do we mispronounce, but then we shorten and change. I had a colleague change one of my students. Her name is Sashacal. She changed. She said, that's just too hard, I'm going to call you Sasha. She changed the child's name. Because of a power dynamic, if it's a college student, you have power over their grades. If it's a parent, you have authority to control over their child.

So when the parents say, my daughter's name is Patrícia and you say, oh, I can't say those R’s, I'm just going to call it Patricia. That parent will say okay because they don't want to upset you when you have control over the child all day.

Marnetta: But then they're going to say things behind. That relationship is damaged. That's it.

Rosemarie: Isn't that the truth? Then people make fun of people's names. You have to understand the history. You have to understand when Africans were brought over to this country, their names were stripped from them. Our last names, to this day, are our slaveholders’ names. They are slaveholders’ names.

I just love these young black girls who are saying, I'm going to name my baby what I want. We have to accept that, but not only that. When people came over to Ellis Island, they Americanized their names, they've changed the spelling of their names. They did a lot to assimilate. Those young people today, do you know they're going to court to reclaim the original spelling and intonation of their names?

Marnetta: It's so beautiful.

Rosemarie: Yes, these names are really, really amazing. So that's an act of bias. Another act of bias is being afraid of the neighborhood where you work. Because when you're afraid of the neighborhood, you're afraid of all the support systems of that child and that family lean on. An active bias—we don't think about this because we're not trained to look at it—is when you're in a diverse early childhood classroom, when you allow white children to have dominance and control over children of color, even in play.

Marnetta: Yeah, we talked about that in our Interactions at the Heart of Healing and Banking Time trainings. You would be surprised with the conversations that happened around that. Whether it's, “What are you talking about? Why would I point that out? Why is that a problem?” It's been so interesting.

Rosemarie: It's such a problem.

Marnetta: Yeah, trying people to understand.

Rosemarie: When you think about it, white children haven't had the model. Think about it. Think about your schools. For most of a white child's life, they have only seen people of color in positions that serve them. They don't see them as teachers. They don't see them as administrators. They see them as bus drivers, cafeteria workers, and front office workers.

This is no one's fault. Remember, there's no blaming or shaming, but we have to unveil this. Because they've never had a person of color in a position of authority, then it elevates them as the authority telling other people what to do and how to serve them. They learned that early and they can learn that in our classrooms if we don't stop it.

Marnetta: Mispronouncing names, deciding you're not going to say that right,—all of those behaviors that you mentioned, children are watching, listening, and learning as you're modeling without even remembering that you are modeling. Because teaching doesn't happen just when you say, “It's on now, all right.” It’s in all the things that you do, once you cross that threshold, once you enter the campus. Children see you and they see your behaviors, how you treat people, what you're doing. It shifts, changes, and builds on their foundation.

Rosemarie: Absolutely. We teach children how to treat children. A friend of mine was telling the story about a child that she had who was a handful. One day, a little girl hit this boy and she goes, “Why did you hit him? We don't hurt our friends here.” The little girl looked at her and said, “Why do you care? You don't like him either.”

Marnetta: Oh, see that? That is exactly what I'm talking about. That's a powerful example and it happens all the time.

Rosemarie: All the time. I had a white mother tell me that her child's teacher was teaching her that black boys were bad. As I dug deeper into the conversation, because I couldn't believe a teacher would teach that, she said, “It's the way that she speaks about them….Duwan is in trouble. Akhmed is in trouble.” At first, they were in trouble and then it turns out that three or four weeks until the year, “They're bad, mommy.”

That's another act of bias when you weaponize children's names. “Duwan, stop. Duwan, don't. Don't make me come over here.” It's teaching children who the troublemakers are in our classroom and they'll treat them accordingly.

Marnetta: Yeah. I could keep on going, but I know that we're almost short on time. Darlene, I apologize because I could keep on going. Do you want to wrap it?

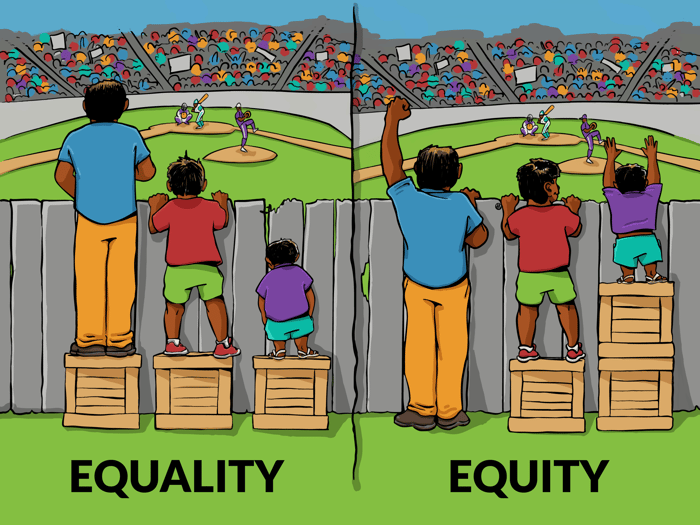

Darlene: No, thank you. I hope you will keep having these rich conversations like this. I know that we are also deeply appreciative of this conversation. Dr. Allen, there is so much more we can talk about. Marnetta and I are like, we can keep going all night with you because we've just touched and just crashed the teeny tiny surface. As you were talking, I couldn't help but think about that image we all like to throw up on the PowerPoint or into a presentation of the children in front of the ball field.

Interaction Institute for Social Change | Artist: Angus Maguire

Interaction Institute for Social Change | Artist: Angus Maguire

I think about how we've been looking at that for a long time, but it seems like we still get confused, equal, and equitable because we keep giving everyone an equal dose instead of thinking about those barriers, the resources, and all those other things that could keep us going in a whole another direction. But I think the good news is we've got a start and we have an opportunity to do it differently in a way that we may not have had before.

So, we need to keep elevating the conversation to make sure we get it right this time and keep it going. I definitely have a deep appreciation for you coming with us in this conversation and at this moment in time. Knowing that there's a long way to go, but I think together, if we each do our part and hold each other to it, to be accountable and committed, I think we will see a collective impact. There's a long way to go, but we might just move that needle.

We got to just inch it along together. I move an inch. Marnetta you move an inch. And keep it going everybody. Dr. Allen, deeply grateful for this conversation. Hopefully, it will keep sparking others to come back to it and do those equity audits.

Rosemarie: May I also say, Darlene, I love that you brought up the graphic for the difference between equality and equity. I just want us to consider equity as an action word. That equity is a verb. Equity is what we do because we want the outcome for all children to be justice.

Darlene: I love that. That's a great, great thing to hold on to. Marnetta, I'm going to let you wrap us, but oh, what a great thought. Thank you, Dr. Allen.

Marnetta: I think that quote could frame all the things we do. I love it. Lots of great takeaways. Dr. Allen, again, thank you so much for being here today.

We'll post the transcription and related resources on our site, teachstone.com\impacting. See you next episode when we dig into the deep challenges of recruiting, training, retaining the ECE workforce.

Remember, behind great leading and teaching are powerful interactions. Let's build the culture together. Bye, guys.