“How would you structure your classroom schedule?”

The first time I interviewed for an early childhood teaching position, this question stumped me. As straightforward as it sounds, I hadn’t really thought about it before! There are so many factors to consider: What activities do my students like? How do they learn best? How do I fit in the activities that licensing or my education director think are important? How do I align these with learning standards or my students’ goals? And, realistically, what are my strengths as a teacher?

It’s overwhelming to consider, especially if you’re new to the field. Luckily, I had some great support around me, but even for the most experienced teachers or coaches, it can be hard to decide where to devote your attention for classroom instruction. A 2013 study from researchers at the University of Virginia may help us understand how instructional quality varies across a pre-K day.

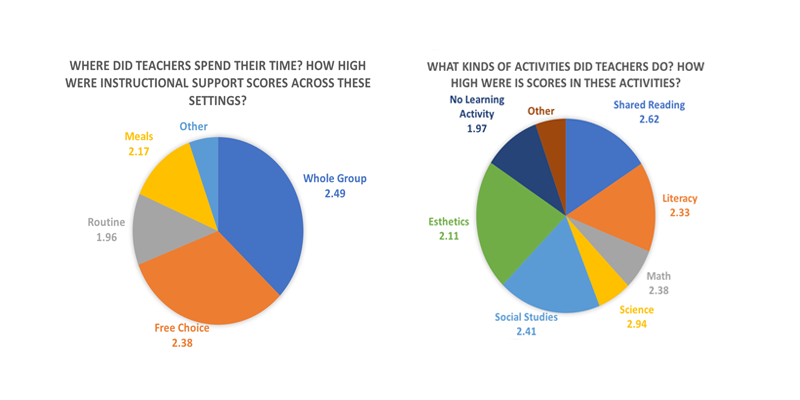

Cabell and colleagues examined instructional effectiveness across different classroom settings (like large group and choice time) and types of learning activities (like science or literacy), with a focus on Instructional Support. Specifically, researchers addressed two primary research questions: to what extent does instructional effectiveness vary across settings and activities? And to what extent are any differences in quality based on setting related to they type of learning activity - essentially, how do these variations overlap?

To look at the quality of Instructional Support, researchers conducted CLASS observations in 314 Head Start and community center classrooms, most of which served low-income students. The teachers in these classrooms were diverse: almost half were African American (45.5%), about a third were Caucasian (31.8%), 12.4% were Hispanic/Latino, and Asian-American and multi-ethnic teachers each made up approximately 3% of the sample. During these observations, data was also collected on two primary predictors: classroom setting (large group, free choice, meals, or routines) and type of learning activity (shared reading, literacy, math, science, social studies, and esthetics).

Researchers also considered several other related factors, including Head Start affiliation, public school affiliation, years of experience, years of education, early childhood specialization, classroom poverty level, class size, proportion of three-year-olds in the classroom, and teacher reports of problem behaviors.

So what did they find? Teachers were observed to have the highest levels Instructional Support during free choice and large group, followed by meals and then by routines. Examining the individual dimensions of Instructional Support showed further variations. Concept Development scores were highest in large group settings, followed by free choice, and the lowest scores for this dimension were observed during meals and routines. Quality of Feedback was highest and comparable during large group and free choice, followed by meals, and routines were related to the lowest scores. Finally, Language Modeling scores were comparably high across large group, free choice, and meal settings, and routines were once again associated with the lowest scores.

Researchers also found associations between the type of learning activity and instructional quality. Dimensions in Instructional Support had the highest scores during science activities and lowest scores when esthetics activities or no learning activity occurred during the observation period. The next-highest Instructional Support scores were associated with shared reading activities, followed by literacy, math, and social studies activities. In addition to science activities, shared reading was related to the highest Concept Development scores. Interestingly, the lowest Language Modeling scores also occurred during math activities - there was not a significant difference in language scores during math and when no activity at all was observed!

To answer the second research question, they examined the overlap between setting (this time, only large group and free choice) and learning activity and explored their relationships with Instructional Support. For most content areas, there were no real differences in Instructional Support scores between large groups and free choice. In both settings, science activities were associated with the highest levels of Instructional Support, and once again, esthetics activities had the lowest scores.

There are a couple of caveats to these findings. In general, the Instructional Support scores in this study were in the low or low-mid range, even in the settings and content areas with the highest scores. These low scores are pretty typical in early childhood settings, and even more so in programs serving low-income students. For example, even though Head Start programs have high averages for Emotional Support and Classroom Organization dimensions, Instructional Support scores are typically in the low-mid range. Additionally, not all teachers were observed in all settings or types of learning activity, which might affect the data. Like anyone else, teachers might spend more time doing activities and sharing content they know they’re good at! Finally, there were some settings and activities that just weren’t observed enough to include, like small groups, which may lead to different outcomes. But without a large enough sample, it’s hard to say how Instructional Support differs.

So how can practitioners incorporate this research? Change is hard! With so many different components, understanding how quality varies across a school day could help programs target professional development. Quality of instruction was context-specific. Seeing the links between what and how you’re teaching and how effective it is might help teachers hone in on areas for improvement. For example, knowing that, on average, esthetics activities produced lower Instructional Support scores, teachers can focus on improving their use of questioning during art centers. Alternatively, they can draw upon their strengths from science activities and think about how they might transfer this support of higher-level thinking skills to other types of learning.

Rather than facing the daunting - and inefficient - task of overhauling instructional practices, this study provides evidence for teachers, coaches, and programs to make targeted, manageable improvements to the quality of instruction in preschool classrooms.

Citation: Cabell, S.Q., DeCoster, J., LoCasale-Crouch, J., Hamre, B.K., Pianta, R.C. (2013). Variation in the effectiveness of instructional interactions across preschool classroom settings and learning activities. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 28(4). 820-830.