I have a rant.

But before I rant, let me tell you a story.

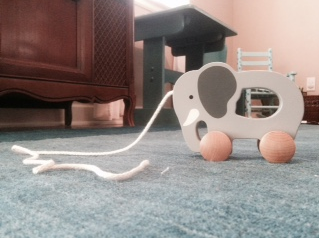

A little after my daughter’s first birthday, she was playing with a small, elephant pull toy. She would try to push it, but it would get stuck on the attached string. After that happened a few times, she tried to bunch the string up and put it on top of the elephant. That didn’t work, so then she tried putting the bunch of string in the hole on the elephant. That failed too. Finally, she decided to put the string over her shoulder while she pushed. The string stayed and she was able to push the elephant, unencumbered.

I tell this story neither to brag about my daughter (although of course I think she is fabulous!), nor to talk about how I tried to implement CLASS-based interactions during this moment (a little parallel talk here, a “what else might you do?” there). I tell it because it demonstrates something about children’s cognitive capabilities: at 13 months, my daughter was problem solving.

So here is my rant …

I think we underestimate children’s cognitive abilities. There are lots of reasons we do this, many of which are completely valid. We are afraid of pushing our children too hard. We want to allow for children’s varying development. We don’t want to lose focus on important social and emotional development.

There is one reason, though, that I think we can change: our definition of “academic” skills.

Often, we confuse academic skills with facts or the amount of knowledge a child has. He can count to 20. She knows the letters in her name. He knows all of his shapes and colors. While these are important pieces of content knowledge for children to have, I wouldn’t define them as academic skills.

But when you look at the definition of academic (or academy), several words stand out.

- Critical ability

- Scholarly pursuit

- Work to support art, science, and literature

All of these phrases show that academic knowledge is more about critical thinking, problem solving, creating new ideas, analyzing, evaluating, comparing, expressing curiosity, engaging in inquiry—I could go on.

When we think about academics in terms of specific pieces of knowledge, we get stuck in teaching through rote methods and never give children the chance to amaze us with what they can know and do.

So, I propose that we redefine the term “academic.” Instead of thinking about facts, let’s think about children’s emerging cognitive abilities (watch here and read more here). Let’s give them opportunities to question, explore, and problem solve. Let’s give them words for their thoughts and encourage them to express what is going on in those precious, little brains. Let’s stop underestimating children and start letting them astound us.

I would love to hear your thoughts.

How have the children you work with amazed you with their cognitive abilities? How might you redefine “academic” skills? What impact would that make on your work with children?