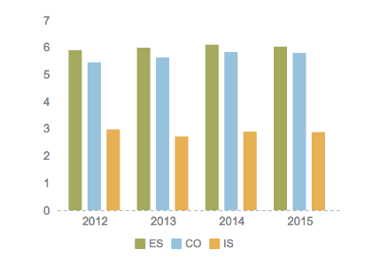

If you’ve ever been to a CLASS training, you’ve probably seen a graph showing a sort of “state of the union” for CLASS scores, the range of scores in each domain that we typically see in pre-K to third grade classrooms across the country. The peak of the curve for Emotional Support sits proudly right between mid and high quality. Classroom Organization is not too far behind it, on the high side of mid. But the Instructional Support curve looks like a sad little turtle in the race to high quality, smack dab in the low range. You can see this in the graph below which shows the average CLASS scores in Head Start pre-K classrooms.

If you’d like to improve Instructional Support in your preschool center or classroom, you’re in very good company. Preschool educators across the country are trying to do the same thing and it seems to be the hardest domain to budge.

Looking at the CLASS in science

Some of our research in Head Start preschools might offer some insight. In one study, Dr. Janna Kook videotaped twenty-four Head Start teachers while doing four different types of instructional activities: circle time, a storybook reading, a math activity, and a science activity. Then, she had reliable CLASS observers code the videos and look at the different kinds of questions that teachers were asking.

She found that while the Emotional Support and the Classroom Organization scores were very similar across these different types of activities, Instructional Support scores were higher in the science activities, compared to all the other activities. Of particular note, Concept Development scores during science activities were, on average, more than a point higher than in circle time.

Teachers in this study had different levels of experience and training in teaching science; some of them were receiving professional development in using a science curriculum but some were not. Interestingly, this did not make a difference. Further, teachers did all kinds of science activities: testing which objects would sink and float in water, estimating the number of cups of water it takes to fill a bottle, discussing plant growth and seasons, mixing different colors in water, making models of the ocean, observing and drawing shadows, and racing toy cars down different heights of ramps. So, what was the common denominator?

What is it about science that makes for higher scores?

Doing good science means analysis, reasoning, explaining your thinking, and discussing your ideas, which is exactly what high quality instructional support encourages kids to do! Research tells us early science is a natural way to get children learning as they explore, observe, make predictions and discoveries; in short, discover and learn about the world around them. The great thing about science is that experimenting is a huge part of the process; this means that we don’t always have all of the answers. In fact, trying something, seeing that it does not work, and talking through and figuring out the possible solutions is what science is all about.

Think about a “sink and float” activity. You might compare a ping-pong ball and a marble, how they feel in your hand and what they do when you put them in the water. You might look at some different objects, like a wood block and a foam block and make some predictions about what they’ll do in the water. You might think back to what you’ve seen before to explain why you think these objects will sink or float. You might write down your predictions, test out the objects, count, categorize, and compare items in both categories, and see if the outcome lines up with what you thought or if you have to revise your thinking. That activity alone calls for concept development, language modeling, and feedback that promotes high-order thinking skills and language use—just imagine all of the fun extensions that you and your class can come up with!

Using executive functions and doing science

Unlike activities that rely on the recall of information or repetition of question-answer routines (e.g., “Hello, class! What is the weather outside today?”), a good science activity means generating new questions, comparing, reasoning, and reflecting.

As you go through an investigation, children use cognitive processes that help them inhibit prior beliefs (e.g., “I think bigger things are always heavier…”), pay close attention to the different characteristics of objects (e.g., “This beach ball is big but feels light in my hand…”), and remember all of the pieces of information as they make, and then check, their predictions.

These cognitive processes are known as executive functions, and they impact learning across all domains as well as interactions with people, materials, and new experiences in the world outside the classroom. We know that children rely on executive functions to do math, literacy and science. Our own research suggests that kids need and rely on executive functions even more for science than for literacy and math!

What’s the take-away?

So what does this mean? It doesn’t mean that teaching science all day every day is the solution for higher CLASS scores. But it does suggest that it might be worth it to incorporate science into your day if you’re not already. And if you’re already teaching science, you might want to think about the ways that you’re supporting children in analyzing and reasoning during science activities.

Of course, there are a lot of science-related activities that happen in preschool classrooms that don’t necessarily provide good opportunities for concept development. Kids might get really excited to watch a caterpillar turn into a butterfly, and they might even learn the difference between a cocoon and a chrysalis, but if they’re not talking about the why and how, comparing, classifying, predicting and evaluating, then they’re not developing a rich conceptual understanding. There are a lot of great curricula and resources out there for teaching preschool science. Our encouragement to you is to try it out, and have fun doing science and exploring and learn right along with your kids!

LEADING AUTHOR

Irena Nayfeld, PhD. has worked as a practitioner and researcher in the field of early childhood and elementary education for over 10 years, with a focus on the development and implementation of engaging, science-based teaching strategies in traditionally under-served settings. Currently, she is building her very own inquiry-driven classroom as a second grade teacher in Brooklyn, N.Y. Prior to this, she worked at Rutgers University and the University of Miami to develop science-based curricula and to assess how these curricula impact teachers and students' socioemotional and academic development. As a postdoctoral fellow at Stanford University's Graduate School of Education, she also worked with educators around the country to develop and assess core teaching competencies of pre-service teacher candidates. Irena is passionate about working with children, parents, and educators to build high-order conversations, critical thinking, and curiosity through instruction that is rich, engaging and fun.

Irena Nayfeld, PhD. has worked as a practitioner and researcher in the field of early childhood and elementary education for over 10 years, with a focus on the development and implementation of engaging, science-based teaching strategies in traditionally under-served settings. Currently, she is building her very own inquiry-driven classroom as a second grade teacher in Brooklyn, N.Y. Prior to this, she worked at Rutgers University and the University of Miami to develop science-based curricula and to assess how these curricula impact teachers and students' socioemotional and academic development. As a postdoctoral fellow at Stanford University's Graduate School of Education, she also worked with educators around the country to develop and assess core teaching competencies of pre-service teacher candidates. Irena is passionate about working with children, parents, and educators to build high-order conversations, critical thinking, and curiosity through instruction that is rich, engaging and fun.

CO-AUTHOR

Janna Fuccillo Kook, PhD. has been conducting research in Head Start centers since 2006 and has been a CLASS PreK trainer since 2009. She is currently a Senior Research Associate at Education Development Center in Waltham, MA where she conducts research on professional development for early childhood teachers in math and science, as well as research in middle school science education. Her research interests include STEM learning, development of higher-order thinking skills through interactions with teachers, and mastery motivation. Janna has a BA in Psychology and Biological Basis of Behavior, and an MS and PhD in Applied Developmental Psychology.

Janna Fuccillo Kook, PhD. has been conducting research in Head Start centers since 2006 and has been a CLASS PreK trainer since 2009. She is currently a Senior Research Associate at Education Development Center in Waltham, MA where she conducts research on professional development for early childhood teachers in math and science, as well as research in middle school science education. Her research interests include STEM learning, development of higher-order thinking skills through interactions with teachers, and mastery motivation. Janna has a BA in Psychology and Biological Basis of Behavior, and an MS and PhD in Applied Developmental Psychology.

CONTRIBUTING AUTHOR

Veronica A. Fernandez, PhD, has extensive experience in early care and education, both as a practioner and researcher. She comes from a family of early educators; in fact, her mom owned and directed a preschool for over 25 years, where Veronica worked while growing up. After obtaining a B.S. in education, specializing in varying exceptionalities and with a TESOL certification, she taught there as a preschool teacher and then served as a curriculum specialist. She is involved in and leads various advocacy efforts at the local, state and nation levels. Veronica obtained an MS and Phd in Developmental Psychology. Her research centers around understanding and improving the quality of early learning experiences of infants, toddlers and preschoolers. She is reliable on the Infant, Toddler and PreK CLASS and is certified as an affiliate trainer. She is currently on faculty at the University of Miami and serves as a senior research consultant to Teachstone.

Veronica A. Fernandez, PhD, has extensive experience in early care and education, both as a practioner and researcher. She comes from a family of early educators; in fact, her mom owned and directed a preschool for over 25 years, where Veronica worked while growing up. After obtaining a B.S. in education, specializing in varying exceptionalities and with a TESOL certification, she taught there as a preschool teacher and then served as a curriculum specialist. She is involved in and leads various advocacy efforts at the local, state and nation levels. Veronica obtained an MS and Phd in Developmental Psychology. Her research centers around understanding and improving the quality of early learning experiences of infants, toddlers and preschoolers. She is reliable on the Infant, Toddler and PreK CLASS and is certified as an affiliate trainer. She is currently on faculty at the University of Miami and serves as a senior research consultant to Teachstone.