My colleagues and I are often asked, “Why do observers have to recertify every year?”

Here are some thoughts on how we arrived at that standard:

- Observing human behavior reliably is really hard. Observing behavior in a complex setting, like a classroom, is especially hard. There are lots of things that can influence what you see and how you code it—what types of activities are going on, which children are present or absent, how you feel that day, how you react to that particular teacher, and so on.

- An “easy” way to reduce all of this complexity is to just ask observers to count things - # of books, # of open-ended questions, # of minutes spent in transition between activities. The problem with this approach is that it captures the things that are easy to count, not the things that are most important for child outcomes (i.e., quantity over quality.)

- The authors of the CLASS measure deliberately sought to focus on the interactions that matter most for children, not the things that are easiest to observe. That resulted in what we call a high-inference tool, meaning that observers have to understand and interpret what they are seeing in order to code accurately.

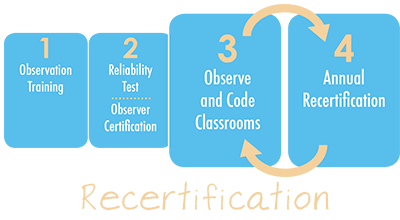

- Because we can't fall back on counting things, we rely on training, certification, recertification, and calibration to keep everyone on the same page with the CLASS master codes. Remember that CLASS master codes aren't just the master coders' opinions about what is best; they are based on decades of research about what children need most from their early childhood experiences. And research with the CLASS shows that, when coded reliably, CLASS scores predict child outcomes.

When we ask people to recertify each year, it is to strengthen their ability to code accurately in the face of all of the influences that might cause them to be unreliable.